In the past thirteen months, my husband has had an excessive number of visits to medical professionals (bladder, back, eyes). We’re calling this summer “the Summer of Repairs,” in hopes that the treatments and surgery he’s gotten since May will start putting him back to rights.

Over these past 13 months, I’ve had a lot of time to study people in the waiting rooms of doctors’ offices and hospitals and to think about the many trials and hopes and expectations of being in limbo while the one you love is being probed and snipped in some other room in the labyrinth. I wrote a blog about one aspect of the medical waiting room (signs of love) a few months ago. Today I want to write about a woman’s face.

Last Tuesday, I was in the waiting room of Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York while Andy had arthroscopic surgery on two herniated discs in his back. It was an unusually nice waiting room—coffee and water, no TV, comfortable chairs, windows overlooking a garden. I was sitting in a little niche by the window, working on my computer, when a surgeon came in to talk to the woman seated across from me.

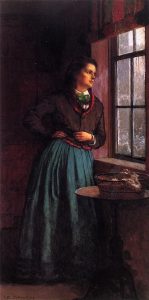

She was an attractive woman in her early-mid 50s, slender, with a good haircut and clothes that were carefully chosen, both in the shops and from her closet. As the surgeon was giving her his news, he stood, while she stayed seated. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but I could tell it wasn’t good from the look on her face. It was the very picture of worry and fear. It seemed that as she listened, she was being poisoned by something much worse than she had anticipated.

A few minutes after the doctor left, I couldn’t help myself. I pushed past my shyness and went over and sat beside her. I told her what I had seen on her face and said that my heart went out to her. She said nothing, just looked at her hands. I told her, “You don’t have to say anything. I just wanted to tell you I hope things will get better.” Then she started weeping. “It’s my son,” she said. I sat with her for a few minutes without speaking, then went back to my seat. Then I heard her making a phone call and telling someone that they had removed the tumor and the surrounding lymph nodes.

She left soon after. About an hour later she came back and bent over me, and thanked me for speaking to her. I have no idea if I gave her any comfort. I just knew I had to offer it.

Seeing that woman’s face, so raw and open in her reaction to the shaking of her world made me realize once again what tender creatures we all are… and how well we usually keep that tenderness hidden.

What I’m Reading

Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar. I first read this book by the Angentinian author about 35 years ago, when I was dating a Brazilian man who introduced me to the extraordinary world of Latin American literature. It’s a challenging novel—155 chapters divided between the story of an intellectual trying to find himself and snippets of philosophy, quotations, diversions, and the reflections of an author who is Cortazar’s stand-in. You can read the novel straight through, as you would a regular book, or you can “hopscotch” between the first part and the second part, following the author’s pattern: for example Chapters 73-1-2-116.

A Savory Moment

Andy’s back surgery was a success. We left the hospital six hours after checking in, walked a few blocks, ducked into a coffee shop as a thunderstorm began and had lunch, took a taxi back to our friends’ apartment. They were both still at work. Andy lay down to take a nap, and I took a long, long bubble bath in the most divine old tub as the rain pattered against the window and I luxuriated in the relief of a one more big, scary procedure having gone well.